Jane Austen's Contributions to Women's Financial Independence

As a place to start, I'd like to ask how many people saw the twitter account Gender Pay Gap Bot (@PayGapApp) on International Women's Day? Epic, right!?

For those who are not addicted to your twitter feed, this is an account that was set up to do exactly one thing – troll twitter for UK registered companies who made some post about how great their company is for women on International Women's Day, and reply with that company's gender pay gap. The information they used to make these tweets is public record in the UK. Starting in 2017, any company registered to do business in the UK with more than 250 employees is required to calculate their raw gender pay gap and report it annually to the UK Government Equalities Office. It is literally just what is the average salary paid to women and the average salary paid to men, no context, no questions, nothing but the raw numbers. There is a lot of good that has come from the gender pay gap reporting and also some legitimate criticism, but to solve a problem, we have to know the extent of the problem.

No matter your position on the policy of the gender pay gap reporting scheme in the UK, you have to go see the absolute chaos crated by the Gender Pay Gap Bot. At least one company deleted their entire social media account on multiple platforms after the bot tweeted out that their PUBLISHED gender pay gap was more that 80%. My biggest question is HOW? How in all that is holy can a company with at least 250 employees have a pay gap that big? This isn't some small mom and pop shop with a handful of employees. These companies have to have at least 250 employees.

So, what has me thinking about all of this? Well, March is Women's History Month, and I am currently sitting in my hotel room during a break at a professional conference and retreat for women with a large group of like-minded female colleagues acclaiming women's accomplishments and encouraging each other for another year of kicking butt in a predominantly male field. It's been inspiring and exhausting at the same time. While there is a lot to celebrate and seeing the successes of my fellow women is a huge boon to my mental health, there's also a familiarity to the state of women in the workplace which feels stagnate. We seem to sit here every year and talk about the same problems: being silenced in the workplace, sexual harassment, having to share credit with male counterparts/bosses, being paid less for the same work, having employers and colleagues ask when we're going to be having the next baby, being passed over for promotions, not getting invited to the golf weekend, few to no women in positions of power in our communities and workplaces ……. Fifteen years after I entered the professional ranks, I don't know if we can say that we've really moved the needle.

Sure, a lot has changed for women in the last couple generations. My life and opportunity as a 30-something working mom is drastically different than my mother's and my grandmother's. But somedays feel like we're not moving nearly fast enough. I don't want the next generation to still be watching whatever the equivalent of a twitter bot will be shame companies for empty proclamations of support for marginalized groups without doing any of the work necessary to reduce the harms caused by such marginalization.

So, here's my work. I want to take this platform which has been shared with me by the women (and a couple of guys) who came before me, women who have done their part raising the voices of new, mostly female, writers, and talk about how the stigma of women's work affected Jane Austen and continues to affect women writers today.

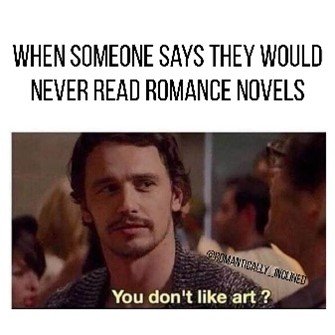

How many times have you heard someone say something derogatory about romance novels? That they aren't "real books" or that they create unrealistic expectations for men in relationships, "chick-lit", "word-porn", "vapid", "frivolous". So many negative connections to romance. It's very popular in intellectual circles to be seen as above reading such "drivel". I've even seen it on social media. Some #bookstagram accounts are solely about the latest literary fiction and excludes anything that looks like an easy read women's fiction novel. Of course, there are plenty of account that are solely dedicated to romance and erotica, but the bookish accounts with 10K+ followers tend to be really curated away from romance. Fantasy is fine, mystery and sci-fi is fine, but romance is still considered as lesser from the literary critics.

Forget the fact that, according to the Alliance of Independent Authors (https://selfpublishingadvice.org/what-readers-want-2022/ ), romance and erotica is the #1 selling genre in the world. Well over a billion dollars in just 2021. That’s more than Crime/Mystery PLUS Sci-Fi/Fantasy PLUS Horror.

Why do we deride romance? I think it's a lot like McDonalds. Everyone wants to be seen as above eating at McDonalds. However, it's painfully obvious that they sell billions of hamburgers each year. So, either they have a philosopher's stone and can turn rocks into gold, or everyone is lying. I'm going to raise my hand right now and say, I eat at McDonalds. Not every day, not even every week, but if I've had a really bad day, chicken McNuggets are probably going to make an appearance in my life.

This opinion, that romance was beneath the serious intellectual, has its roots in the late 18th and early 19th century. Exactly the time that Jane Austen was writing her novels.

While there are earlier examples of female writers and novelists (see Love in Excess by Eliza Hayward), Jane Austen is one of the very first women to write in the style of realistic romance. The defining characteristics of realistic romance are a story centered on the development of the relationship between two or more people without the interference of fantastical or magical elements. It may seem like a simplistic definition, but it was very new at the time Austen was writing. Most of the popular romance novels at the turn of the 19th century centered on gothic elements (ex: Mrs. Radcliff's The Mysteries of Udolpho) or followed the main character – most often a man – through some harrowing life journey while trying to get back to his faithful love in the style of Homer's Odyssey. Stories about women, their lives, and their struggles, were virtually nonexistent when Austen started writing.

One significant reason for this was that a woman with a profession was seen as vulgar. Women were supposed to be wives and mothers, not working outside the home. Having a woman in your family as a published writer would have been scandalous. During her lifetime, all of Austen's novels were published anonymously. It was only after her untimely death in 1817, when her brother Henry published her last two completed novels together, that he wrote a "Biographical Note" at the end of the book naming his sister as the author of all six published novels. As we have learned over and over again, representation matters. If you keep an entire group of people from telling their story, it will never be told correctly. Men cannot tell women's stories.

Austen's writings are riddled with references to the state of women's opportunities and education in her own time. Not overtly, but just peppered into her novels every now and again. Take this exchange between Anne Elliott and Captain Harville at the end of Persuasion:

“I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman’s inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of woman’s fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men.” (Captain Harville)

“Perhaps I shall. Yes, yes, if you please, no reference to examples in books. Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.” (Anne Elliott, emphasis added)

Austen's novels, like romance novels today, were significantly more popular with women of the time than men. The stories, which centered women's lives and lived experiences, resonated with the educated upper class women of the 18th century. There was something of every lady in an Austen heroine. Therefore, Austen's novels were largely ignored by reviewers at the time and if given any publicity at all, typically lauded as good reading for young women with strong moral value. This stigma, that women's romance novels are just fluffy tripe, continues into today.

Even the circumstances surrounding how Austen was able to sell and publish her books tells an interesting story that highlights how stories about women were belittled. Her first finished novel, Northanger Abbey – which was originally titled Susan, was sold to a London publisher for only £10. Though there were promises made, it was never printed and distributed. She had to buy back the copyright in 1816, well after the 4 novels published in her lifetime had seen success. Her second novel, the first to be actually published, Sense and Sensibility, was taken on commission, where the publishers would advance the costs of publication, repay themselves as books were sold and then charge a 10% commission for each book sold, paying the rest to the author. If a novel did not recover its costs through sales, the author was responsible for them. It is not well documented whether Austen preferred this method after her experience with Susan, but we do know that the Austen family was not very well off, especially after her father's death. It would have been a hardship had the book failed.

After Sense and Sensibility was profitable, the publisher then purchased the copyright for Pride and Prejudice outright, paying Austen a whopping £110. As a comparison, S&S, again published at Austen's peril, was produced using "expensive paper and sold for 15 shillings". However, P&P, published using the publisher's money, was produced using "cheap paper and sold for 18 shillings." Austen could have made nearly £500 if she had been given a commission on P&P. (see: Irvine, Robert; Jane Austen. London: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-31435-6)

Austen was popular in her own time, but never made significant money from her works. The number of copies printed was small compared to other contemporary popular authors, and reprintings were not common at the time. She was known in some circles for her work, but hardly respected. Never able to do anything without one of her brothers playing the intermediary.

A funny, but all too familiar for women today, example of never gaining true respect is the advice (mansplaining) offered to her by the Prince Regent's librarian, James Stanier Clarke. In November 1815, Austen was invited to visit the Prince's London residence as he was a fan of her novels. She felt she could not refuse the invitation though she disapproved of Prinny's licentious lifestyle. Shortly after her visit, Austen wrote a diatribe called Plan of a Novel, according to Hints from Various Quarters (https://pemberley.com/janeinfo/plannovl.html). This satiric outline of the "perfect novel" was based on the Clarke's many suggestions for a future Austen novel. My favorite bit goes as follows:

"Wherever [the heroine] goes, somebody falls in love with her, and she receives repeated offers of Marriage -- which she refers wholly to her Father, exceedingly angry that he should not be first applied to."

It's clear in these words that Austen was completely fed up with the feminine ideal created by men of her class and era. Unfortunately, this is a sentiment that many women today are still bemoaning.

Though our world continues to show signs that women are not viewed universally as equal to men, and the struggle for advancement is real, I want to end this post on a positive note.

Women all over the world are making ourselves heard. Most women toady can own property, open bank accounts, and make a really good living without the approval of any father, husband or brother. The advance of careers like self-publishing romance novels has given freedom to countless women. The ability to make money from our own artistic pursuits cuts out the power dynamics of the traditional workplace. More women are taking on "side-hustles" which turn into full time careers and lead to financial independence. Financial independence of women is the number one metric of social mobility according to the UN. When women begin earning a living wage, communities start to see rapid growth in healthcare infrastructure, access to education, and decreases in childhood mortality from food instability.

Maybe it doesn't matter that "serious literary critics" call romance novels trash. As long as women continue to write our own stories, we will eventually silence the naysayers. One book at a time, we will command billions of dollars and leave a better world for our daughters.